‘Another pointless interview’. A report from Russia’s Astrakhan region, where the climate crisis and government indifference are accelerating a once-lush ecosystem’s desertification

Manage episode 512304128 series 3381925

Astrakhan is famous throughout Russia for its watermelons and produce, but it could soon be known instead as a lifeless desert. That prognosis might sound alarmist, but the once-flourishing region is already being swallowed by the sand. This summer, journalists from the independent media outlet Kedr traveled to towns in the Astrakhan region that are suffering the most severe effects of desertification. They spoke with residents about what it means to survive under such conditions and asked ecologists what factors, apart from climate change, are exacerbating the situation in southern Russia, and if there are any ways to mitigate the impact of what has already begun.

A dense, gray-brown column of dust stretches across a front hundreds of yards wide. The “cloud,” as tall as a five-story building and driven by fierce winds, blankets houses and roads, clawing at windows. Nothing is visible behind it or inside it. It can advance relentlessly for hours without losing momentum. When it finally settles, it leaves behind layers of sand.

This is what it’s like to experience a dust storm. In Astrakhan, these storms are no longer rare.

In the common imagination, the Astrakhan region is usually associated with lush abundance: juicy watermelons and trophy fish catches. Few Russians are aware that this entire ecosystem is facing extinction as the desert encroaches.

The United Nations considers desertification one of the gravest environmental threats to the planet. U.N. data show that 2 billion people live in arid regions, with land degradation rates now 30-35 times higher than in past centuries.

Desertification is currently advancing across one-quarter of Astrakhan’s territory — encompassing 1.3 million hectares (more than 5,000 square miles). An additional 2 million hectares (7,720 square miles) are at risk. People are abandoning their gardens because nothing can grow in the baking sand. They’re also giving up on fishing as bodies of water dry up. A correspondent from Kedr traveled to the region to document the catastrophe and learn how locals are adapting to life in an environmental disaster.

Read more about the receding Volga

‘Nobody’s coming to help’

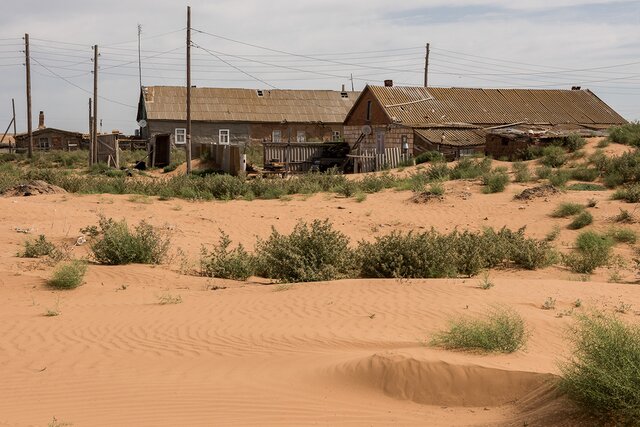

Roughly 100 kilometers (62 miles) west of Astrakhan, we veer from the main highway into the steppe. Outside the vehicle, the heat has reached a scorching 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit). The steppe begins to recede, giving way to sand dunes and tufts of camelthorn. Eventually, we come to Barkhany, a one-road, mostly deserted town.

Barkhany once had its own store, medical clinic, and community center. During Soviet times, residents raised livestock and grew melons here, with irrigation water pumped from the Volga through an artificial canal. “It was good here,” says a woman named Albina, who’s come to town to bring groceries to her mother-in-law. Shyly, she speaks briefly with Kedr after seeing our car pull into town. “After the Soviet collapse, the collective farm disappeared, and the sands came. Desertification began. Dust storms would rise up so thick you couldn’t see anything. People would dig themselves out, but the wind would bring sand again. Many gave up.”

We drive on and encounter a couple herding a flock of sheep into a courtyard. Shulpan has lived in Barkhany for 60 years and used to work at the town store. Rising sands have swallowed half her home, and a wooden board separates the remaining living area from the space reclaimed by nature. Shulpan recalls the past fondly but is reluctant to discuss life today. “We’ve given up hoping for anything,” she tells Kedr. Local officials have also abandoned the town, and she can’t remember the last time the district’s supervisor set foot in Barkhany. “The only help we really get is the rain.”

The canal that fed water to Barkhany was closed down when the town’s state farm was dissolved. Officials struggle to explain this decision, but the district attempted in 2018 to plant saxaul throughout the town, hoping to replenish the livestock-ravaged greenery and reinforce soil structure to combat desertification. However, these perennial shrubs soon died, and officials blamed locals for allowing their animals to graze on them. People in Barkhany reject these allegations.

The collective farm protected Barkhany from desertification through the Volga Canal water and land improvement systems, which artificially moistened the area. There was more rainfall, too. In 2018, for example, the entire Astrakhan region didn’t get a single drop of rain throughout the spring or during the first half of summer.

Shulpan becomes animated when the subject turns to a district initiative to resettle Barkhany’s population in rooms at a former orphanage in a nearby town. “Even after the [Second World] War, they didn’t try stuff like that,” she says. “I worked my whole life, built up something for myself, and now I’m just supposed to walk away from it all? Over there, we’d all be packed in tiny little rooms like sardines.” The thought of waiting in line to use a shared kitchen also enrages her. “Even their water is nasty. Ours is actually cleaner, though we have to have it trucked in.”

As Shulpan speaks, a man walks by and interjects: “Another pointless interview. Nobody’s coming to help us.”

Another woman emerges from a neighboring house, clad in a headscarf, thick sunglasses, and camouflage clothing to shield herself from the punishing sunlight. She says she spoke once before in 2015 to a local television news crew about Barkhany’s struggles. “We had this kid with cerebral palsy living here with his mom, and we only went on camera and told them how we’re living out here because of him, not for our own sake,” the woman told Kedr. “We wanted the government to pay attention. But nobody lifted a finger to help.”

In the end, “a volunteer from Moscow” bought the family a place to live, but “people still laugh at us today,” the woman says, still hurting a decade later.

An older man joins our conversation and describes his predicament: “At least we’ve got livestock, while those who don’t even have that are going off to fight in the special military operation. They buy houses, cars, and live decent lives. But I’m too old, I can’t run around, and over there you have to keep moving so you don’t get…”

“Tokhta,” the woman interrupts him, using the Kazakh word for “stop.”

Read more about Russia and climate change

‘What can we do about the animals?’

Deserts have existed in the Astrakhan region and in neighboring Kazakhstan for thousands of years. They’re a perfectly natural landscape for the area, but their displacement of steppe ecosystems presents a critical problem for the human population. Astrakhan ecologist Stanislav Shinkarenko notes that there are two primary causes of desertification in the region: global climate crisis and more local human activity, including uncontrolled grazing.

People living in Astrakhan have spent roughly two centuries battling desertification. Early efforts relied on drought-resistant plants. The Soviet government launched a program to create forest belts to counteract drought conditions and sand encroachment. Officials also introduced hydrology infrastructure and soil-protective crop rotations. These mitigation strategies significantly reduced dust storms on farmland, says Shinkarenko, but the decline of Russia’s agriculture sector by the 1990s meant an end to much of the work on expanding and upgrading the irrigation and tree-planting systems.

In 2022, Governor Igor Babushkin said 80 percent of the Astrakhan region’s pastures had been depleted, partly due to livestock grazing practices.

An environmental scientist in Astrakhan, who requested anonymity, told Kedr that the region historically relied on nomadic grazing that spread livestock evenly across pastures. During the Soviet era, however, collective farming and stricter state control eventually molded Astrakhan’s livestock management into a fixed system in which animals were no longer driven across long distances.

“Now all the lands are divided into shepherd points, where livestock comes every evening, trampling the same trails,” says the local scientist. “Vegetation doesn’t have time to recover.”

In Astrakhan’s Narimanov district, the steppe is dotted with solitary houses that offer shelter to shepherds and modest enclosures to pen their livestock. When we turn off the highway, we see herds of animals wandering in search of scarce grass. We stop near one group of sheep and meet a shepherd who switches off his motorcycle to watch his flock. The man says he’s been driving livestock for four years.

“There’s just not enough grass, and it keeps getting worse all the time,” he says reluctantly. “Whatever’s left gets buried under sand. The wind’s always blowing it around.”

Pressed on the subject, he admits: “Yeah, sure, the animals trample the grass too, but what can we do? We have to get by somehow.”

“Climate changes are such that moisture conditions will keep getting worse. We should expect further degradation of the Volga floodplain and delta,” says ecologist Stanislav Shinkarenko. “At the same time, we’re seeing a significant increase in days with high wind speeds, so the situation could soon become irreversible. At the very least, we need to start regulating livestock numbers according to pasture capacity and begin implementing vegetation restoration measures.”

According to biologist Lyudmila Yakovleva, who studies desertification, only 3 percent of livestock farmers systematically recultivate the land they use by reseeding after grazing, fertilizing with compost or manure, or covering the soil with plant residues to enrich the soil organically. “Overgrazing during droughts causes catastrophic effects,” says Shinkarenko, including massive dust storms that “dramatically increase areas of exposed sand and areas without vegetation cover.”

‘We’re bathing in green water’

Russia’s Narimanov, Ikryaninsky, and Liman districts are home to some 120,000 people. In the past, the area has teemed with shallow lakes known as the Western Sub-Steppe Ilmens (ZPI). These seasonal bodies of water only fill during spring floods, but they serve as the local population’s main water source.

Today, many of these shallow lakes exist only on maps, replaced by salt flats. “If areas aren’t flooded regularly due to limited water supply, you get soil salinization and degradation,” an Astrakhan ecologist told Kedr.

In the town of Kurchenko in Astrakhan’s Narimanov district, the seasonal lake has dried up. Blue barrels with taps have appeared in some local stores: drinking water for sale.

“You saw it yourself — it’s all dried up over there, and on the other side it’s all gross and slimy with reeds growing everywhere,” says a woman named Adel, when asked about Kurchenko’s ilmen. “When it gets hot, a nasty, rotten smell rises from it. Everything we tried to grow this year just died. The smart people have stopped planting gardens altogether.”

In 2021, Russia’s Ministry of Emergency Situations acknowledged the region’s water shortage, confirming that the shallowing of the Volga delta had left 10,000 people in three Astrakhan districts without adequate water. Drawing on ethnic ties, Astrakhan Tatars living in the Narimanov district even appealed to Tatarstan head Rustam Minnikhanov, hoping to draw attention to the problem. While the campaign to raise awareness continues to this day, conditions have not improved.

In the town of Nikolayevka, Kedr meets a woman who introduces herself as Raisa. “They bring us drinking water to the stores twice a week, on Tuesdays and Saturdays. But for everything else…” she says, pointing to a thicket of reeds. Sure enough, among the slime and duckweed, there is a shallow body of muck, glimmering in the sunlight. A putrid smell fills the air.

This swamp is part of the ilmen that stretches along the town. In the center, the lake looks better with more open water. At a nearby playground, children run around carrying empty five-liter jugs. Across the street, a group of adults crowds near a local grocery store. When asked about the water situation, they all start talking over each other.

“You can’t brush your teeth or use the banya,” complains a woman named Tatyana. “We’re bathing in green water. Sometimes, we wash our clothes and they come out smelling rotten. What century are we living in? I watch these elderly women hauling jugs of water to the store, and it just breaks my heart. I’m recovering from surgery myself, and it’s hard to carry water.”

Nikolayevka’s seasonal lake is muddy and warm. When some people in the crowd insist that it’s possible to walk across it entirely without sinking, a man in a blue shirt volunteers to demonstrate. He wades into the shallow water and trudges about 20 yards in from the shoreline, the water barely reaching his knees.

“When I was young, there was so much water that we never even had to buy fish. Somebody would come back from a day’s fishing, knock on your window, and say, ‘Here, take some fish.’ These days, when they bring fish to the store, people immediately post about it in the neighborhood chat. It’s like a big event for us,” says a woman named Zemfira.

The people of Nikolayevka have also appealed to the governor and even sent a representative to Moscow to try to meet with President Putin. “Everybody knows about the water problem. But nothing ever changes. It’s like they’re deliberately trying to kill off our towns,” says a blonde woman in dark glasses.

Russia’s nature struggles

That’ll be the day

The Volga is indeed growing shallower. The Earth’s rising temperatures affect its delta ecosystem, but a more immediate factor is the Volga’s upstream water flow, which depends entirely on the eight hydroelectric power stations operating along the river. According to ecologist Evgeny Simonov, the limited water releases currently in effect are insufficient to fill floodplain lakes, causing them to dry out and salinize:

Hydroelectric dam construction fundamentally changed the river’s natural flow patterns. Instead of powerful spring floods, we got “special water releases” at volumes many times smaller. There’s nowhere near enough water to make it out to the far edges of the delta, especially those western sub-steppe lakes.

Many seasonal lakes dried up completely, and others became salt marshes due to a lack of water flow and salt accumulation. Remaining water stagnates and blooms, killing fish and destroying spawning areas. More than 20 percent of the floodplain area faces direct desertification.

Oceanographer Vladimir Androsov has studied Astrakhan’s seasonal lakes for more than two decades. He became interested in their disappearance after encountering unexpected problems while planning a fish farm in the area. One of the first red flags for Androsov was the quota ceiling on his fishing license — a mere 24 tons, just a fraction of the fishing hauls he knew were common in the Soviet era.

“So I started digging into why there’s no fish anymore,” Androsov told Kedr. “It all comes down to one thing: these shallow lakes completely depend on the water that flows in during spring flooding. Today, water and fish simply can’t get into the lakes.”

The lakes also serve as “natural reservoirs” that maintain water levels in the western part of the Volga delta. Androsov learned that spring floods replenish the region’s groundwater, which cools the lakes, preventing algae and reed growth, and stopping fish from dying off in these waters during the spawning season.

This creates a vicious cycle: the weakening Volga can’t fill the lakes, while these systems prove incapable of sustaining river levels. The lake area has already shrunk by 40 percent in size since the hydroelectric cascade was built. Prospects for the remaining 60 percent look bleak, given the Volga’s continued water level decline.

“The only way to fight desertification is to get the natural water channels working again,” Androsov says. “All we have to do is release the full amount of water that all these dam structures are holding back.”

Ecologist Evgeny Simonov acknowledges that full flood water releases would hurt the power industry’s bottom line, as hydroelectricity generation requires high reservoir levels. However, he argues that the Volga hydroelectric plants play a relatively minor role in the country’s unified power grid, and the lost capacity could be offset with sufficient political will.

Viktor Danilov-Danilyan, head of the Institute of Water Problems at the Russian Academy of Sciences and a former environment minister, agrees with Simonov’s assessment. Danilov-Danilyan estimates that the power grid would need to make up about 3-4 gigawatts of capacity if the Volga’s hydroelectric plant operations were reduced due to environmental concerns. “That’s equal to one good gas-fired power plant. We have nowhere to put our gas right now anyway,” the scientist says.

“The damage from depleted fish populations, pasture degradation, and water supply problems far exceeds the energy sector’s profits,” reasons Evgeny Simonov. “The government must prioritize environmental water releases over industry profits — it’s a strategic security issue. Technically speaking, we’re perfectly capable of releasing more water.”

In mid-July, Kedr attended festivities for Fisherman’s Day in Astrakhan, where people flock to the Petrovskaya embankment of the Volga. For the celebration, districts from across the region set up stands to serve local products, like watermelons and traditional soups.

At the very end of the exhibition row, there’s a tent manned by army recruiters. In the distance, from the festival’s main stage, the lyrics of a song drift in the air:

We’ll live, never die. We’ll weather the storm. / Spread wider, Mother Russia. Make way, keep us warm. / They say the men will all soon disappear — / But our foes will never see that day come here.

Story by Kedr

Adapted for Meduza in English by Kevin Rothrock

64 episodes